Every time someone takes a medicine, there’s a silent system working behind the scenes to watch for problems. This isn’t science fiction-it’s drug safety monitoring, a global network that catches harmful side effects before they become epidemics. Think of it like a worldwide early warning system for medicines. When a new drug causes unexpected liver damage in Brazil, or a vaccine triggers rare blood clots in Sweden, this system is what finds it-and then tells doctors and regulators everywhere.

How the Global System Works

The backbone of international drug safety monitoring is the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring (PIDM), launched in 1968. It’s not a single agency. It’s a network of over 170 countries, each running its own national center to collect reports of bad reactions to medicines. These reports-called Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs)-are sent to a central database called VigiBase, managed by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) in Sweden.As of 2023, VigiBase held more than 35 million reports. That’s a huge jump from just 5 million in 2012. Each report includes details: what drug was taken, what side effect happened, when, and who reported it. But here’s the key: these reports aren’t proof that the drug caused the problem. They’re clues. The real work is in spotting patterns across thousands of reports from different countries.

That’s where standardization matters. Every report uses the same language: MedDRA, a medical dictionary with over 78,000 terms for symptoms and conditions. Drugs are coded using WHODrug Global, which tracks over 300,000 medicine names. Reports are sent electronically using the E2B(R3) format. Without these standards, the system wouldn’t work. A reaction reported as "dizziness" in one country and "lightheadedness" in another would never connect. Standard terms make the connections possible.

Regional Systems: EU vs. US vs. Global

Not all systems are the same. The European Union runs EudraVigilance, a tightly regulated system that requires drug companies to report adverse events within 15 days. It’s fast, detailed, and legally binding. The EU’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) reviews signals within 75 days on average-much quicker than the global average of 120 days.The U.S. has FAERS, the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System. It gets about 2 million reports a year, but it’s separate from the WHO system. The U.S. does send some data to VigiBase, but it’s not fully integrated. That means a safety signal found in Europe might take weeks to appear in U.S. databases, and vice versa.

The WHO system doesn’t have legal power. It can’t force a country to act. It can’t recall a drug. Its job is to detect signals and alert member countries. That’s why it’s so valuable: it sees what no single country can. For example, the Dengvaxia dengue vaccine was found to increase risk in people who’d never had dengue before-first noticed in the Philippines. That signal would’ve been missed without data flowing from low-income countries into VigiBase.

The Big Problem: Who Reports, and Who Doesn’t

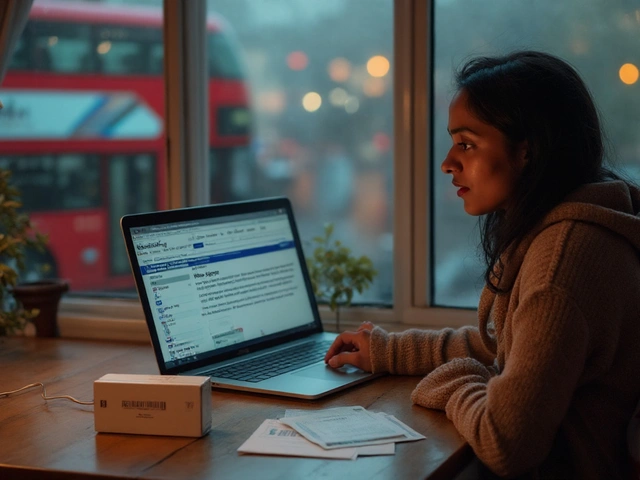

There’s a massive imbalance. Countries with high incomes-just 16% of the world’s population-submit 85% of all reports to VigiBase. Sweden reports about 1,200 adverse events per 100,000 people each year. Nigeria? About 2.3 per 100,000. That’s not because Nigerians don’t have side effects. It’s because their systems lack resources.In many low-income countries, pharmacovigilance budgets are under $0.02 per person annually. In high-income nations, it’s over $1.20. Many clinics don’t have internet. Staff haven’t been trained. Some don’t even have forms to fill out. A WHO study found that only 42% of low- and middle-income countries have systems meeting basic global standards. That’s a huge blind spot. A dangerous side effect could be killing people in rural India or rural Kenya-and the world wouldn’t know until it shows up elsewhere.

Even when systems exist, they’re often slow. Ethiopia cut reporting time from 90 days to 14 after using a web tool called PViMS. But only 35% of health centers there submit reports regularly-mostly because of poor connectivity. In Southeast Asia, nearly 70% of pharmacovigilance officers have had less than 15 hours of formal training. WHO recommends 40.

How Technology Is Changing the Game

The field is evolving. Artificial intelligence is now helping sift through millions of reports to find real signals. UMC’s AI system cut false alarms by 28% in 2023. That means fewer distractions and faster action on real dangers.Electronic reporting is growing fast. In 45 low- and middle-income countries, new tools for vaccine safety have cut reporting time from two months to just seven days. The UK’s Yellow Card app lets doctors and patients report side effects in seconds. Over 78% of healthcare workers use it. That’s real-time surveillance.

And soon, a new global standard called ISO IDMP will roll out. It will make sure every medicine is identified the same way everywhere-by name, ingredients, manufacturer, dosage, even packaging. Right now, a drug called "Paracetamol" in one country might be listed as "Acetaminophen" in another. IDMP will fix that. Experts say it could improve cross-border matching of side effects by 40%.

Who’s Responsible?

It’s not just governments. Drug companies are now legally required to monitor their products after they’re sold. The top 50 pharmaceutical companies each have dedicated pharmacovigilance teams averaging 250 staff-up from 150 in 2018. They pay for it because the cost of missing a safety issue can be billions in lawsuits and lost trust.But the real heroes are the frontline workers: nurses who notice a patient’s unusual reaction, pharmacists who ask patients about new symptoms, and doctors who fill out a simple form. These reports are the raw material of global safety. Without them, the system is silent.

What’s Next?

The system is getting stronger. More countries are passing laws that require pharmacovigilance. Since 2015, 85% of WHO member countries have made it part of national law. Ukraine restarted its center in March 2023. Yemen joined in 2022. Zanzibar became a member in early 2024.But sustainability is still a problem. One-third of low-income country systems rely on donor money. If funding dries up, their systems collapse. The WHO Global Benchmarking Tool shows 28% of countries still have no formal system at all.

Public access is also improving. VigiAccess lets anyone-patients, researchers, journalists-search anonymized data from VigiBase. Over 12 million people have used it since 2015. That transparency builds trust.

Drug safety monitoring isn’t perfect. But it’s the best thing we have. It’s how we learned that thalidomide caused birth defects, that Vioxx increased heart attack risk, and that some COVID-19 vaccines could trigger rare blood clots. Each time, the system worked-because people reported, systems collected, and data was shared.

It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t make headlines. But every day, it’s preventing harm. And that’s what matters.

What is pharmacovigilance?

Pharmacovigilance is the science of detecting, understanding, and preventing harmful side effects from medicines. It includes collecting reports from doctors, patients, and pharmacies, analyzing them for patterns, and taking action-like updating labels or pulling drugs off the market-to protect public health.

How does VigiBase work?

VigiBase is the World Health Organization’s global database for adverse drug reaction reports. National centers in over 170 countries submit electronic reports using standardized formats. These reports are coded with medical terms and drug names, then analyzed for unusual patterns. If a signal is found-like a rare side effect appearing in multiple countries-the WHO alerts member nations to investigate.

Why do rich countries report more adverse reactions?

High-income countries have better infrastructure: trained staff, electronic reporting tools, public awareness campaigns, and funding. In places like Sweden or the UK, healthcare workers are encouraged and equipped to report side effects. In low-income countries, many clinics lack internet, forms, or even basic training. It’s not that fewer reactions happen-it’s that fewer are recorded.

Can I access drug safety data myself?

Yes. The WHO offers VigiAccess, a free public portal where anyone can search anonymized data from VigiBase. You can look up a drug and see what side effects have been reported globally. It’s used by patients, researchers, and journalists to understand potential risks.

What’s the difference between the WHO system and the EU’s EudraVigilance?

The WHO system is a voluntary global network focused on detection and information sharing. It has no legal power. The EU’s EudraVigilance is a legally binding system with strict deadlines for reporting, mandatory reviews by experts, and authority to recommend regulatory actions across all 27 EU member states. The EU system is faster and more detailed but covers fewer countries.

Are AI tools really making drug safety monitoring better?

Yes. Traditional methods looked at reports one by one, which took time and missed subtle patterns. AI can scan millions of reports quickly, flagging unusual combinations of drugs and side effects that humans might overlook. UMC’s AI system reduced false alarms by 28% in 2023, helping experts focus on real threats faster.

What happens after a safety signal is detected?

Once a signal is confirmed, the WHO alerts member countries. National regulators then investigate locally-reviewing medical records, running studies, or checking if the issue is widespread. If confirmed, they can update drug labels, issue safety warnings, restrict use, or withdraw the drug. Sometimes, no action is needed if the risk is too small to outweigh the benefit.

How can I report a side effect?

If you’re in a country with a national pharmacovigilance system, you can report through official channels. In the UK, use the Yellow Card app or website. In the U.S., go to the FDA’s MedWatch portal. In many countries, your doctor or pharmacist can file a report for you. Even if you’re unsure if the drug caused the reaction, report it. Your report could help save someone else’s life.

gerard najera

3 January, 2026 . 02:32 AM

Systems like this work because humans care enough to report. Not because of tech or laws. Just ordinary people noticing something’s off and saying something.

That’s the real magic.

Stephen Gikuma

3 January, 2026 . 16:35 PM

Let me guess - the WHO’s just a front for Big Pharma to bury real side effects while pushing more vaccines. You think they’d let a global database expose their profits? Come on.

FAERS is rigged. EudraVigilance? Same game. They only report what they want you to see. The 85% from rich countries? That’s not data - that’s propaganda.

They don’t want you to know how many kids got brain damage from ‘safe’ meds. They just want you to keep taking them.

And don’t get me started on AI ‘fixing’ signals - that’s just noise suppression. They’re not finding patterns, they’re deleting them.

Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s control dressed in white coats.

Bobby Collins

4 January, 2026 . 09:43 AM

ok but what if the AI is actually being trained to ignore certain side effects? like… what if it’s coded to not flag stuff that makes pharma look bad?

i mean, who writes the algorithms? big pharma employees??

also why is VigiBase so slow to update if it’s ‘real-time’? someone’s hiding something. i feel it.

and why do we even trust Sweden? they’re not even in NATO anymore??

just saying… 🤔

Layla Anna

5 January, 2026 . 09:15 AM

Wow this made me tear up a little 😭

It’s wild to think that someone in a village in Nigeria might be the first to notice a deadly reaction… but no one ever hears them.

I just used the Yellow Card app last week after my cousin had that weird rash - felt like I did something real.

And VigiAccess? I looked up my mom’s blood pressure med and found 3 other people had the same issue. I didn’t know I could do that.

We need more tools like this everywhere. Not just in rich countries. Everyone deserves to be seen.

Thank you for writing this. Really.

💛

Heather Josey

6 January, 2026 . 18:06 PM

This is one of the most important public health infrastructures you’ve never heard of - and it’s working. Despite underfunding, lack of training, and systemic inequities, the global pharmacovigilance network continues to prevent harm on a massive scale.

It’s not perfect, but it’s the only system we have that connects local experiences to global action.

Every report matters - whether it comes from a hospital in Stockholm or a clinic in Kigali.

Investing in low-resource systems isn’t charity - it’s self-preservation. A side effect ignored in one country becomes a crisis everywhere.

We must prioritize equitable funding, digital access, and training. This isn’t optional. It’s foundational to global health security.

Donna Peplinskie

7 January, 2026 . 08:53 AM

I just love how this system, despite all its flaws, still gives a voice to people who otherwise wouldn’t be heard…

And the fact that you can search VigiAccess as a regular person? That’s revolutionary…

It’s like the internet finally did something good for public health…

But you’re right - the gap is terrifying…

Imagine being a nurse in rural Zambia, seeing five patients with the same reaction, and having no way to send it out…

We need translators, mobile apps, solar-powered reporting stations…

And we need to stop treating this like a ‘developing world problem’ - it’s a human problem.

Everyone deserves to be protected…

Even if they live somewhere with no Wi-Fi…

❤️

Olukayode Oguntulu

7 January, 2026 . 12:26 PM

Let us not be fooled by the epistemological façade of pharmacovigilance as a neutral, objective apparatus. The very architecture of VigiBase is a colonial artifact - a metropole-centric epistemic hegemony where the Global South is reduced to data points, not agents.

MedDRA? WHODrug? E2B(R3)? These are not neutral taxonomies - they are instruments of linguistic imperialism, erasing local phenomenologies of adverse events under the guise of standardization.

The 85% reporting disparity is not a failure of infrastructure - it is a deliberate ontological exclusion.

AI algorithms trained on Western-centric datasets? They are not detecting signals - they are reinforcing the epistemic violence of Northern hegemony.

Until we decolonize pharmacovigilance, we are merely automating surveillance, not justice.

And the ‘heroes’? Nurses? Pharmacists? They are not heroes - they are expendable cogs in a machine that commodifies suffering.

True safety lies not in reporting, but in dismantling the structures that render some lives reportable and others invisible.

jaspreet sandhu

8 January, 2026 . 14:43 PM

You people talk about VigiBase like it’s some kind of miracle but you forget that most of the reports come from places where people are already over-medicated and under-informed - so of course they report more side effects, because they’re on ten pills a day and don’t know what’s normal.

In India, people take paracetamol for headaches, then ibuprofen, then a herbal tea, then a steroid cream, then a vitamin supplement - and then they get dizzy and say it’s the medicine.

But you don’t know that. You just see a report and say ‘signal!’

And you think AI can fix this? No. AI just makes it worse - it finds fake patterns because the data is garbage.

And don’t even get me started on the WHO - they’re just a bureaucracy that loves to send emails and hold meetings.

The real problem? Doctors in villages don’t even know what a side effect is. They just give pills and send people home.

So you want to fix this? Train the doctors. Not build more apps. Not hire more AI engineers. Train the people who actually see the patients.

Everything else is just noise.

Alex Warden

9 January, 2026 . 21:14 PM

Let’s be real - the U.S. has the best system in the world. FAERS might be messy, but it’s ours. We don’t need some Swedish database telling us what’s safe.

And why are we sending our data to the WHO? They don’t even have a seat at the UN Security Council.

Meanwhile, the EU is demanding 15-day reports - that’s ridiculous. Who has time for that?

And don’t even get me started on Nigeria reporting 2.3 cases per 100k - that’s not a lack of infrastructure, that’s just people not complaining.

Our system works because we’re not afraid to say ‘this drug is dangerous’ and pull it.

Other countries? They’re still waiting for permission.

We lead. They follow. Simple.

LIZETH DE PACHECO

10 January, 2026 . 13:12 PM

Thank you for writing this - I’ve never seen a post that explains pharmacovigilance so clearly.

I used to think side effect reporting was just paperwork… now I realize it’s how we protect each other.

My aunt had a reaction to a new antibiotic last year - her doctor filed the report. I didn’t even know that was an option.

So I just downloaded the Yellow Card app and reported my own weird headache after a new supplement.

It took 90 seconds.

And I felt like I did something real.

If you’re reading this - please, take 2 minutes. Report something.

You might save a life.

And if you’re in a country without a system? Tell someone. Push for it.

This isn’t about governments or AI - it’s about us.

And we’re better than we think.