What Is Lower GI Bleeding?

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding means blood is coming from somewhere in your colon or rectum. You might notice bright red blood in your stool, or it could look like maroon-colored stool. Sometimes, the bleeding is slow and hidden - you might just feel tired, dizzy, or short of breath because your body is low on iron. This isn’t the same as upper GI bleeding, which usually causes black, tarry stools. Lower GI bleeding is common, especially after age 60. About 1 in 5 cases of all GI bleeding happens in the lower tract, and it’s one of the top reasons older adults end up in the hospital.

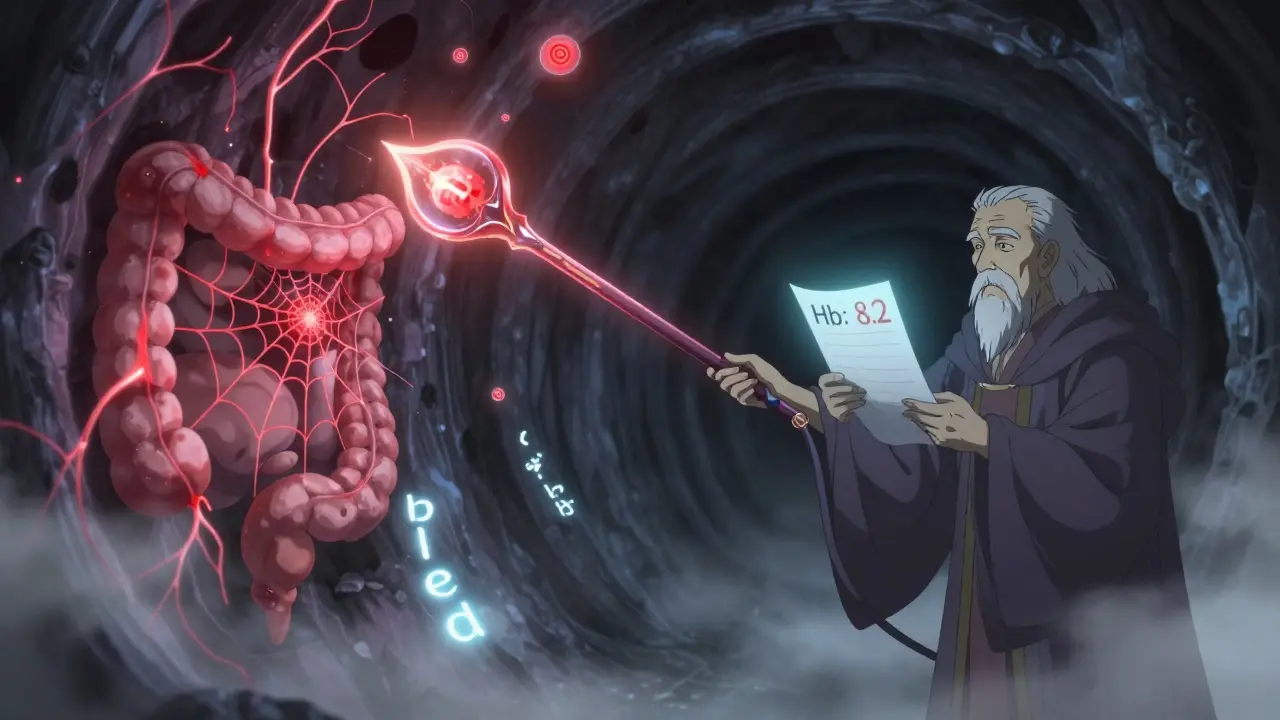

Two Big Culprits: Diverticula and Angiodysplasia

Most of the time, when someone has lower GI bleeding, it’s because of one of two things: diverticula or angiodysplasia. They’re both common in older adults, but they work very differently.

Diverticula are small pouches that stick out from the wall of your colon. They form over time as the muscle layer weakens, especially in the left side of the colon. These pouches aren’t dangerous by themselves - most people have them and never know. But sometimes, a blood vessel runs right over the top of one of these pouches. When that vessel gets irritated or bursts, you get sudden, heavy bleeding. It’s often painless, which makes it scary. People describe it as just looking down and seeing a lot of bright red blood in the toilet. About 30% to 50% of all serious lower GI bleeds come from diverticula.

Angiodysplasia - also called vascular ectasia - is when small blood vessels in the colon become twisted, enlarged, and fragile. These aren’t true tumors or cancers. They’re just abnormal blood vessels that form because of aging, especially in the right side of the colon. Unlike diverticula, angiodysplasia rarely causes sudden, massive bleeding. Instead, it leaks slowly over weeks or months. That’s why people with this condition often show up with anemia - they’re tired, pale, and weak - before they even see blood in their stool. About 3% to 6% of lower GI bleeds are from angiodysplasia, but it’s the second most common cause after diverticula in people over 70.

How Doctors Figure Out What’s Causing the Bleed

When someone shows up with GI bleeding, the first thing doctors do is check if they’re stable. If blood pressure is low or heart rate is high, they start fluids and blood transfusions right away. Then comes the diagnostic hunt.

The first test is almost always a complete blood count (CBC). If your hemoglobin is below 10 g/dL, that’s a sign you’ve lost a lot of blood. They’ll also check your clotting factors and kidney function. Next comes colonoscopy - and it needs to happen fast. Studies show that doing a colonoscopy within 24 hours of bleeding cuts death risk by nearly a third compared to waiting 48 hours or more. You don’t need a perfect bowel prep in an emergency. Doctors often give you IV fluids and a drug called erythromycin to speed up clearing out the colon so they can see clearly.

During the colonoscopy, the doctor looks for the source. Diverticula show up as small bulges with a clot or red spot on top. Angiodysplasia looks like red, spiderweb-like patches, often near the cecum. If they find the source, they can treat it right then - with clips, heat, or epinephrine injections.

But here’s the catch: sometimes, the colonoscopy comes back clean. That happens in up to 30% of cases. When that occurs, doctors turn to other tools. CT angiography is great if you’re still bleeding. It can spot active bleeding as slow as half a milliliter per minute. It’s fast, non-invasive, and works even if you’re too unstable for colonoscopy. If you’re stable but the bleed keeps coming back, they might use capsule endoscopy - you swallow a tiny camera that takes pictures as it moves through your intestines. It finds the cause in about 6 out of 10 cases. But it’s not perfect. About 1 in 7 people have a capsule that gets stuck, especially if they have undiagnosed narrowing in the bowel.

How They Treat Each Cause

Not every bleed needs surgery. In fact, most stop on their own.

For diverticula bleeding, about 80% of cases stop without any treatment. Doctors just give you fluids, monitor you, and maybe give you a blood transfusion. If it keeps bleeding, they go back in with a colonoscope and use a combination of epinephrine injections and heat (thermal coagulation). This stops the bleeding in 85% to 90% of cases. But here’s the downside: about 1 in 4 people will bleed again within a year. If it keeps happening in the same spot - say, the sigmoid colon - they might recommend removing that section of the colon.

Angiodysplasia is trickier. It doesn’t usually bleed hard, but it bleeds often. The go-to treatment is argon plasma coagulation (APC). It’s like using a fine jet of gas and electricity to burn the abnormal vessels shut. It works right away in 80% to 90% of cases. But the problem? It doesn’t last. Up to 40% of people bleed again within a year or two. That’s why some patients end up having multiple procedures.

For those with repeated bleeding, doctors now have other options. Thalidomide - yes, the same drug once used for morning sickness - has shown real promise. A 2019 study found that taking 100 mg daily reduced the need for transfusions in 7 out of 10 patients. It’s not approved for this use yet, but many GI specialists prescribe it off-label. Another option is octreotide, a hormone-like drug given as an injection. It helps reduce blood flow to the abnormal vessels. It’s not a cure, but it can help control bleeding between procedures.

For rare, severe cases, surgery is still an option. If angiodysplasia is concentrated in the right side of the colon, removing the right half (right hemicolectomy) often solves the problem. For diverticula, removing the affected segment can prevent future bleeds.

What You Should Know About Long-Term Outlook

The good news? Most people survive their first major bleed. The 30-day death rate for diverticula bleeding is around 10% to 22%, but that’s mostly because patients are older and have other health problems - heart disease, kidney failure, diabetes - not because the bleeding itself is deadly. Angiodysplasia has a lower death rate - 5% to 10% - but it’s more of a chronic burden. People with recurring angiodysplasia often end up in the hospital multiple times a year. Many report feeling frustrated after going through three or four negative colonoscopies before finally getting a diagnosis. That diagnostic delay can take over a year.

Long-term survival is actually pretty good. Five years after a major bleed, about 78% of people with diverticula and 82% with angiodysplasia are still alive. What matters most isn’t the bleeding - it’s your other health conditions. Managing those is just as important as treating the bleed.

What’s New in Treatment?

Technology is helping doctors spot problems faster. New AI tools built into colonoscopy machines can highlight tiny angiodysplasia lesions that human eyes might miss - one study showed a 35% increase in detection. There are also new endoscopic clips designed to clamp down on bleeding diverticula more securely. In a European trial, these clips stopped bleeding in 92% of cases.

Right now, the National Institutes of Health is running a big clinical trial comparing thalidomide to a placebo for people with recurrent angiodysplasia bleeding. Results are expected in late 2024. If it works, this could become a standard treatment.

What Should You Do If You Notice Blood in Your Stool?

Don’t ignore it. Don’t assume it’s hemorrhoids. Even if it stops, get checked. The most dangerous bleeds are the ones that seem to stop on their own - they often come back harder.

If you’re over 60 and you’ve had even one episode of bright red blood in your stool, talk to your doctor about a colonoscopy. If you’re on blood thinners, have heart disease, or have a history of anemia, you’re at higher risk. Ask if you should be screened for angiodysplasia, especially if your anemia keeps coming back.

And if you’ve had a bleed before, follow up. Many people assume they’re fine after one episode. But the risk of rebleeding is real. Keep your doctor updated if you feel weak, dizzy, or notice changes in your bowel habits.

Bottom Line

Lower GI bleeding isn’t normal, even if it happens once. Diverticula and angiodysplasia are the two most common causes in older adults, and they need different approaches. Diverticula bleed fast and hard - but often stop on their own. Angiodysplasia bleeds slow and steady - and can sneak up on you as anemia. Colonoscopy is still the gold standard, but newer tools like CT angiography and AI-assisted scopes are making diagnosis faster and more accurate. Treatment has improved, but recurrence is common. The key is early detection, proper follow-up, and managing your overall health. Don’t wait for the next bleed to act.

Jenna Allison

23 January, 2026 . 01:18 AM

Just had my mom go through this last year. She had a massive diverticulum bleed out of nowhere - no pain, just bright red everywhere. Colonoscopy found it fast because they gave her erythromycin first. They cauterized it and she’s been fine since. But yeah, the fatigue lasted for months. Iron infusions were a game changer. Don’t ignore it, even if it stops. It always comes back harder.

blackbelt security

24 January, 2026 . 05:36 AM

My uncle had angiodysplasia for 5 years before they figured it out. He was anemic, tired, pale - thought it was just aging. Got diagnosed after a capsule endoscopy got stuck. Took 3 procedures and a thalidomide trial to finally stabilize him. It’s not glamorous, but it’s real.

Patrick Gornik

25 January, 2026 . 01:49 AM

Let’s be real - this whole system is a money machine. Colonoscopies? $3k. Capsule endoscopy? $5k. APC? Another $2k. And then they throw thalidomide at you like it’s vitamin C. Meanwhile, the real cause? Industrial food, sedentary lifestyle, and a medical-industrial complex that profits off chronic illness. They don’t want you cured. They want you returning for repeat procedures. The system doesn’t heal. It monetizes suffering. And we’re all just pawns in a blood-soaked spreadsheet.

Tommy Sandri

25 January, 2026 . 07:20 AM

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. The clinical distinctions between diverticula and angiodysplasia are often blurred in primary care settings, leading to diagnostic delays. The emphasis on early colonoscopy within 24 hours is well-supported by current guidelines. The integration of AI-assisted detection represents a significant advancement in endoscopic precision.

venkatesh karumanchi

25 January, 2026 . 15:09 PM

This is so important for older folks. My dad ignored his blood in stool for months - thought it was hemorrhoids. By the time he went in, he was in ICU. Please, if you're over 60 and see red, don’t wait. Get checked. Your body isn’t lying. You just need to listen.

Marlon Mentolaroc

25 January, 2026 . 23:17 PM

Wow. So diverticula bleed like a broken pipe and angiodysplasia is like a slow drip from a leaky faucet. One’s dramatic, the other’s sneaky. And thalidomide? That’s wild. The same drug that caused birth defects now saving people from internal bleeding? Irony doesn’t even cover it. Also, 92% success with new clips? That’s insane. Why isn’t this on every TV ad?

Gina Beard

27 January, 2026 . 18:08 PM

It’s not the bleeding that kills you. It’s the years of ignoring your body until it screams.

Don Foster

28 January, 2026 . 15:15 PM

Colonoscopy is gold standard? Please. That’s what they taught you in med school 20 years ago. CT angiography is faster, less invasive, and detects active bleeding at 0.5 mL/min. And capsule endoscopy? Only useful if you don’t have strictures. Most docs still treat this like it’s 2005. AI detection? Yeah sure, but only if you can afford the new endoscopy units. This system is rigged for the wealthy.

siva lingam

28 January, 2026 . 18:27 PM

So basically, old people bleed and doctors charge them $10k to stop it. Then they bleed again. Then they charge again. And we call this healthcare? I’m just here for the free popcorn.

Phil Maxwell

30 January, 2026 . 01:17 AM

My grandma had angiodysplasia. She’d get transfusions every few months. She never complained. Just said, ‘I’m still here, aren’t I?’ She died at 89. I think she outlasted the bleeding. Honestly, the real hero here is patience. And maybe a good GI doc who doesn’t rush.

Shelby Marcel

30 January, 2026 . 23:03 PM

so like… if u see red in the toilet, just go to the doc? no joke? i thought it was just my period being weird or something. i’m 63 and i just thought i was getting old. damn. i’m making an appt tmrw.

Viola Li

31 January, 2026 . 12:39 PM

Thalidomide? Really? The same drug that caused phocomelia? You’re telling me we’re now prescribing a teratogen to elderly patients because the medical system can’t figure out how to stop slow bleeding without it? This isn’t innovation. This is desperation dressed up as science.

Dolores Rider

1 February, 2026 . 01:34 AM

THEY KNOW. THEY KNOW THE BLOOD ISN’T JUST FROM ‘AGING’. THEY KNOW THE FOOD IS TOXIC. THEY KNOW THE WATER IS CONTAMINATED. THEY JUST DON’T CARE BECAUSE THEY MAKE MONEY OFF THE HOSPITAL STAYS. 😡👁️🗨️💧🩸 #BigPharmaLies

Helen Leite

2 February, 2026 . 07:09 AM

AI detecting lesions? 😱 I swear I saw a TikTok that said they’re putting microchips in colonoscopes to track your bowel movements. Are we being monitored? Is this how they’re building our medical profiles? 🤔👁️🗨️ I’m scared now.

Elizabeth Cannon

3 February, 2026 . 02:56 AM

to anyone over 60 reading this: you are not too old to get checked. you are not a burden. your life matters. if you’ve had one episode of blood in your stool, please, for your own peace of mind - get the colonoscopy. you deserve to feel safe in your own body. and if you’re scared? bring someone. you don’t have to do this alone. i’m here. we’re all here.