Moderate Drinking: What It Means and Why It Matters

When it comes to moderate drinking, the practice of consuming alcohol in amounts that stay within recognized low‑risk guidelines. Also known as light to moderate alcohol intake, it aims to balance enjoyment with health safety. Understanding this balance starts with knowing how alcohol consumption, the total ethanol a person drinks over a period is measured and why dosage matters.

Guidelines from health agencies typically define moderate drinking as up to one standard drink per day for women and up to two for men. A standard drink contains roughly 14 g of pure alcohol – about 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of spirits. This safe limit is not a recommendation to drink daily, but a ceiling that, when respected, keeps most people out of trouble. The key idea is that the body can metabolize a limited amount of alcohol each hour; staying below that threshold reduces the chance of acute effects like impaired judgment.

Health Benefits and Risks Linked to Moderate Drinking

Research on cardiovascular health, the condition of the heart and blood vessels shows a nuanced picture. Some studies suggest that moderate drinkers have a slightly lower risk of heart disease compared to abstainers, possibly because alcohol can raise HDL (good) cholesterol and improve blood vessel flexibility. However, these benefits are not universal – they depend on age, gender, genetics, and lifestyle. For example, moderate drinking may help reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in certain populations, yet it can also raise the chance of certain cancers, especially when consumption exceeds the recommended limits.

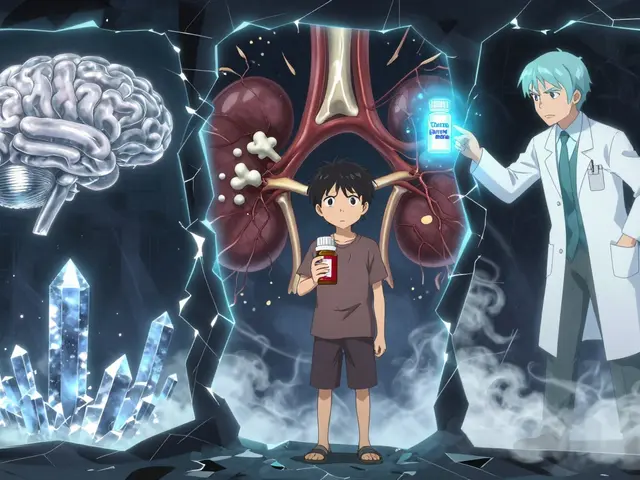

Beyond disease risk, moderate drinking interacts with many common medications. Blood‑pressure drugs like Olmesartan/Amlodipine can be less effective if alcohol spikes blood pressure. Antidepressants such as Wellbutrin or Lexapro may cause heightened side‑effects when mixed with even modest alcohol amounts. Antibiotics like Azithromycin or Tetracycline can irritate the stomach more if you drink while taking them. Knowing these interactions is crucial because a single drink can tip the balance from safe to harmful for people on prescription meds.

Age and personal health status also shape what “moderate” looks like. Older adults often have slower metabolism and may feel the effects of a single drink more strongly. Pregnant women, people with liver disease, or those with a family history of alcoholism should aim for no alcohol at all. The safest approach is to assess your own risk factors, talk to your healthcare provider, and adjust your drinking habits accordingly.

Practical tips can help you stay within the safe zone: use a measuring cup for spirits, count your drinks over a week rather than a single day, and pair alcohol with food to slow absorption. If you notice a pattern of needing more drinks to feel the same effect, that’s a red flag that your limit may have slipped. Substituting non‑alcoholic beverages for some social occasions can keep the habit in check while still enjoying the moment.

Below you’ll find a curated set of articles that dig deeper into specific medicines, health conditions, and lifestyle factors related to moderate drinking. Whether you’re curious about how alcohol affects blood pressure, interacts with antibiotics, or influences mental health, the collection provides clear, actionable info to help you make informed choices.

How Alcohol Affects Ischemia and Your Heart Health

Explore how alcohol influences ischemia and heart health, compare drinking patterns, spot warning signs, and learn practical steps to protect your cardiovascular system.

View More